"Personalized Service, Care and Education is the cornerstone of our practice"

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

TEDxOrangeCoast - Amy Purdy - Living Beyond Limits

Here is a patient of ours Amy Purdy, who speaks on using life boundries as a springboard to enhancing life for yourself and others. That limitations are only limited by your imagination. Watch and gain inspiration from someone who lives, breathes and leads by example.

Bernabe Duran

Thursday, November 17, 2011

Our World: 'Pushed to the brink of what our bodies can be pushed to'

Photo by TRISTAN SPINSKI // Buy this photo

It's a chilly Friday night in Bonita Springs. The bleachers overflow with fans as the stadium lights kick on and eleven softball players jog into right field to warm up. These men have been through hell. They've braved bombs and bullets and shrapnel and rockets and fire. And now they are on a mission: to show that life goes on after war. Outfielder Daniel "Doc" Jacobs, pictured above, 26, flops onto his back to stretch. Jacobs, a U.S. Marine who lives in San Diego, lost his left leg below the knee after being struck by an Improved Explosive Device (IED) during a routine patrol in the Sunni Triangle in Iraq in February of 2006.

It’s a chilly Friday night in Bonita Springs. The bleachers overflow with fans as the stadium lights kick on and eleven softball players jog into right field to warm up. These men have been through hell. They’ve braved bombs and bullets and shrapnel and rockets and fire. And now they are on a mission: to show that life goes on after war.

Outfielder Daniel “Doc” Jacobs, pictured above, 26, flops onto his back to stretch. Jacobs, a U.S. Marine who lives in San Diego, lost his left leg below the knee after being struck by an Improved Explosive Device (IED) during a routine patrol in the Sunni Triangle in Iraq in February of 2006.

After two years in rehab, Jacobs has returned to full duty. Part of his job includes traveling around the country with the Wounded Warrior Amputee Softball Team, a collection of U.S. Army and Marine Corps veterans who have lost limbs post 9/11 while serving their country. The team averages two games a month against police departments and fire departments across the United States. On this night they play the Bonita Springs Fire Department.

Every member of the team has a story. Second baseman Tim Horton, 27, of San Antonio, served two years and eight months with the U.S. Marine Corps, with a full year of that service spent in the hospital after and IED struck his humvee, spraying his body with shrapnel, breaking his wrist, both elbows and taking his left leg below the knee. Horton said after 50 surgeries, he’s stopped counting. What he and his teammates can count on is his athletic ability, which he demonstrated by back-pedaling into center field and a diving catch to end the first inning.

Head Coach David Van Sleet also works for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, specializing in prosthetics. Van Sleet says he put the Wounded Warrior Amputee Softball Team together last spring after marveling at the scope of athletic talent returning from Iraq and Afghanistan with severe injuries.

“After they were injured, they didn’t know if they were going to live,” Van Sleet said. “They didn’t know if they were going to walk again. They didn’t know if they were going to play sports again.”

After much brainstorming, Van Sleet put a national call out to VA hospitals, military bases and other organizations that might point him towards the best veteran amputee athletic talent in the country. Hundreds answered the call. Twenty made the cut.

One of the chosen few was Sgt. Randall Rugg, a 34-year-old native of Monroe, La. who now plays catcher. Rugg served with the U.S. Marine Corps from 1999 to January of 2004. His unit was ambushed on March 22, 2003 in Iraq. Rugg survived five rocket-propelled grenades hitting his vehicle. Like so many of his teammates, he lost his left leg below the knee.

Rugg says his transition to civilian life was difficult. There was no camaraderie. The two jobs he landed upon returning were fraught with office backstabbing. It was every man for himself, Rugg said. So when a representative from his VA called him, asking if he would be interested in playing softball with fellow amputees, Rugg jumped.

“Hell yeah. I’ll be there,” Rugg said.

“It’s therapeutic,” Rugg says. “It’s like being with family. It’s like going home to see mom and dad for the holidays and being around people that love and accept you. It’s the same thing with this.”

“We’ve been pushed to the brink of what our bodies can be pushed to,” he said. “Sometimes my leg - it’s sweaty. It hurts. But the job’s not done. I push it to the end.”

The Wounded Warrior Amputee Softball Team is a nonprofit organization that depends on charitable donations to continue their outreach and advocacy across the United States. If you are interested in learning more or donating to the Wounded Warrior Amputee Softball Team, visit their website: www.woundedwarrioramputeesoftballteam.org, or call: (703) 549-2288.

Teen's goal: Eliminate phantom pain in amputees

Thursday - 11/10/2011, 1:50pm ET

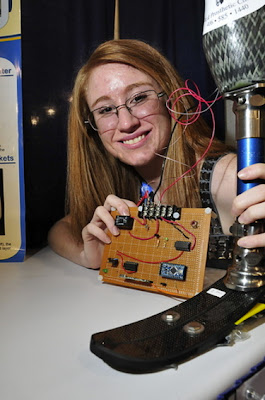

Katherine Bomkamp is seen with her invention, which is designed to eliminate phantom pain felt by amputees (Photo Courtesy of Intel )Darci Marchese, wtop.com

WASHINGTON -- Katherine Bomkamp was struck by what she saw the first time she visited Walter Reed Army Medical Center with her father, a member of the U.S. Air Force.

"Sitting in waiting rooms were all these very young amputees returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. That really got to me. They were 18,19 years old, young kids," she says.

The Waldorf teen, 16 at the time, says she talked to the men and women who had lost their limbs at war about phantom pain -- the pain an amputee feels in the limb that's no longer there. The pain, she says, is "caused by the brain that automatically sends signals to a limb to move. The signals get caught in the severed nerve endings, causing pain."

About the same time as her visits to the hospital, Bomkamp's tenth grade science teacher encouraged the North Point High School students to complete a project that could have an impact.

Bomkamp decided to study phantom pain, hoping to find a way to prevent it without the use of drugs. Over time, she invented a holistic prosthetic device she now calls the "pain free socket," a device that uses heat to force the brain to focus on high temperatures produced through thermal-bio feedback, rather than send signals to the nonexistent limb.

The invention won her several awards at local and national science fairs. But she didn't stop there.

Now a 19-year-old sophomore at West Virginia University, Bomkamp is working to have her device commercialized. She's received one patent for the "pain free socket" and says a major prosthetic company has expressed interest in it. She's even created her own company.

She credits the university for helping her develop the device and to raise funding for it.

"Before I came to WVU, this was a project. But now it's become a viable product that could go on the market," she says.

"It's come a long way from when I was 16."

Bomkamp is excited to give back to wounded warriors. She says the device will be tested on amputees and she hopes it will be on the market in just a couple of years.

Because of her accomplishments, she becomes the first West Virginia University student to be inducted into the National Museum of Education's National Gallery for America's Young Inventors. And last week, she was named one of Glamour Magazine's "21 Amazing Young Women." The distinction was given to young women across the country for changing the world through service and innovation.

Thursday, November 10, 2011

Finding her stride

Josh Radtke | The State News

Kinesiology senior McKayla Hanson waits for her brother Jacob, 13, to bring up the other handcycle into the driveway after the two finished an afternoon ride. Due to her high amputation, Hanson rides the special type of bike during the running and bicycle portions of the triathlon. She travels to California this week to compete in a half Ironman Triathlon, a stepping stone to the Paralympic games, where she is determined to one day be a competitor.

After her right leg was amputated at age 7, McKayla Hanson gave up on rollerblading, biking and her chances at a normal life.

In elementary school, Hanson, who is now a kinesiology senior at MSU, purposely broke her prosthetic leg to get out of wearing it to class.

Years later, Hanson is walking, biking and rock-climbing.

She’s been training for months to participate in the 2011 San Diego Triathlon Challenge on Sunday and today, she’s leaving for California.

“I hate the fact that most people I see that are physically disabled are either overweight or obese,” Hanson said. “Just because you have a disability doesn’t mean you should eat McDonald’s every day or sit on your butt because your back or leg hurts — you can’t let that get to you.”

“It’s huge for somebody that’s injured,” Long said. “It’s not only getting out; it’s realizing that you can do active activities.”

A step behind

Hanson’s parents put her into foster care along with her sister to give them a chance at a better life.

When Hanson was living with her first foster care family, she began feeling pain in her right leg.

She cried from the pain, but her foster parents told her it was growing pains. A tumor was visible on her leg.

In the Hanson house, where she went next in foster care, that kind of neglect didn’t last.

Her new foster parents, who later adopted her, told her she had a rare form of bone cancer — rhabdomyosarcoma.

From the hip socket and pelvic bone down, Hanson’s right leg had to be amputated.

“I was more happy than scared because of the pain I felt,” Hanson said.

Doctors said she’d never walk again, but her family pushed her to overcome her disability.

“She didn’t have a disability when she was here; she was one of the kids,” McKayla’s mother, Elisa Hanson said. “When it was her time to clean, (she cleaned).”

McKayla Hanson’s mother was by her side the first time she rode a bicycle after cancer claimed her right leg, and now as she’s training for the triathlon this weekend.

“They said, ‘You can either lay in bed and feel sorry for yourself … or you can get up and do something,’” McKayla Hanson said.

“My physical disability has never stopped me since they told me that.”

Leaps and bounds

Although her right leg was gone, McKayla Hanson had the heart of an athlete growing up.

She began swimming in middle school, then began rock climbing and handcycling.

Her athletic career was jump-started when she got a new prosthetic leg from the Challenged Athletes Foundation, an organization that helps raise money for disabled athletes.

“We think it’s something that helps make someone’s life whole and more meaningful,” said Travis Ricks, programs coordinator and athlete relations at the Challenged Athletes Foundation.

“We want them to not feel like there’s something missing in their life.”

With a new leg and ambitions to participate in triathlons, McKayla Hanson began working with a coach on the handcycle — an arm-operated bicycle.

Ray Bailey, a member of the Tri-County Bicycle Association. never taught someone with a disability before and never used a handcycle.

It’s been a learning experience for both of them, but since they started working together, she’s gone from about 9 mph to about 14 mph average on her handcycle — enough to be competition at the triathlon next Sunday, Bailey said.

“I’ve pushed her a little bit, only to the point I can see it on her face,” he said.

McKayla Hanson also rides with the Tri-County Bicycle Association and the Fusion Cycling Team.

To members, it’s more than a way to exercise.

“If we see people are struggling in the cycling community, we kind of like to help,” Bailey said.

Long, who also leads the Fusion Cycling Team, met McKayla Hanson at a race about a year ago.

Getting to know her and other disabled athletes provides support and hope for him.

“You’re learning from someone that’s gone through the same road as you,” Long said.

“You can talk to a lot of people, friends and family, that haven’t gone through a disability, but they can’t really understand unless they’ve gone through it.”

At MSU, McKayla’s studying to become a physical therapist — to give back to the disabled community, as she was helped by others.

“I really would like to work with the disabled community in any way that I can,” she said.

“Whether it be to incorporate more physical fitness for them, start my own organization or anything along those lines, but I really want to work … for those who are physically challenged.”

McKayla Hanson’s training won’t be over when she finishes the triathlon in San Diego.

After that, her training for the 2014 Paralympics begins.

“She’ll take something competitive, not necessarily just a marathon, but get ready for the triathlon and take it to the extreme limit,” Long said.

“She’s a true athlete.”

Wednesday, November 2, 2011

Biotech start-up builds artful artificial limbs

Bespoke Innovations has gone out on a limb by building a new business around a bold idea – that prosthetic legs can communicate a message of personal style more than disability.

In a packed lecture hall at Stanford last week, Scott Summit, Bespoke’s chief technology officer and a Stanford engineering lecturer, told those of us in the audience about his start-up company’s vision — to bring humanity and self-esteem back to people who have suffered traumatic limb loss.

Using a 3D scanner, technicians create a digital image of an amputee’s surviving limb and create a mirror image of that morphology using parametric computer modeling. They feed this data into a laser-powered 3D printer that fabricates a custom superstructure, which can then be adorned with fashion-oriented materials like wood, metal, cloth, and leather. “We can create a personalized limb in 30 hours for about $4,000,” Summit told us.

Both utilitarian and beautiful, the Bespoke staff works with people to customize the designs and materials to reflect individual personality and tastes. Some are finished with ballistic nylon or polished nickel. One was covered in quilted leather, like a Chanel handbag. For a military veteran with a love of tribal tattoos, the team scanned a favorite tattoo design from one leg and fabricated the fairing using that theme. A competitive soccer player who lost his leg to cancer chose an aircraft-like honeycomb design that allowed him to play soccer again.

Summit, who works alongside co-founder Kenneth Trauner, MD, a Bay Area orthopedic surgeon, hinted that his interdisciplinary team of designers, engineers, physicians, and entrepreneurs has other innovations under wraps that will push the boundaries of human prosthetics and be “the coolest things you’ve ever seen.”

A video of the lecture is available on Stanford University’s Entrepreneurship Corner website.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)